KoyaQuest

Life of Kūkai

Life of Kūkai

Life of Kūkai

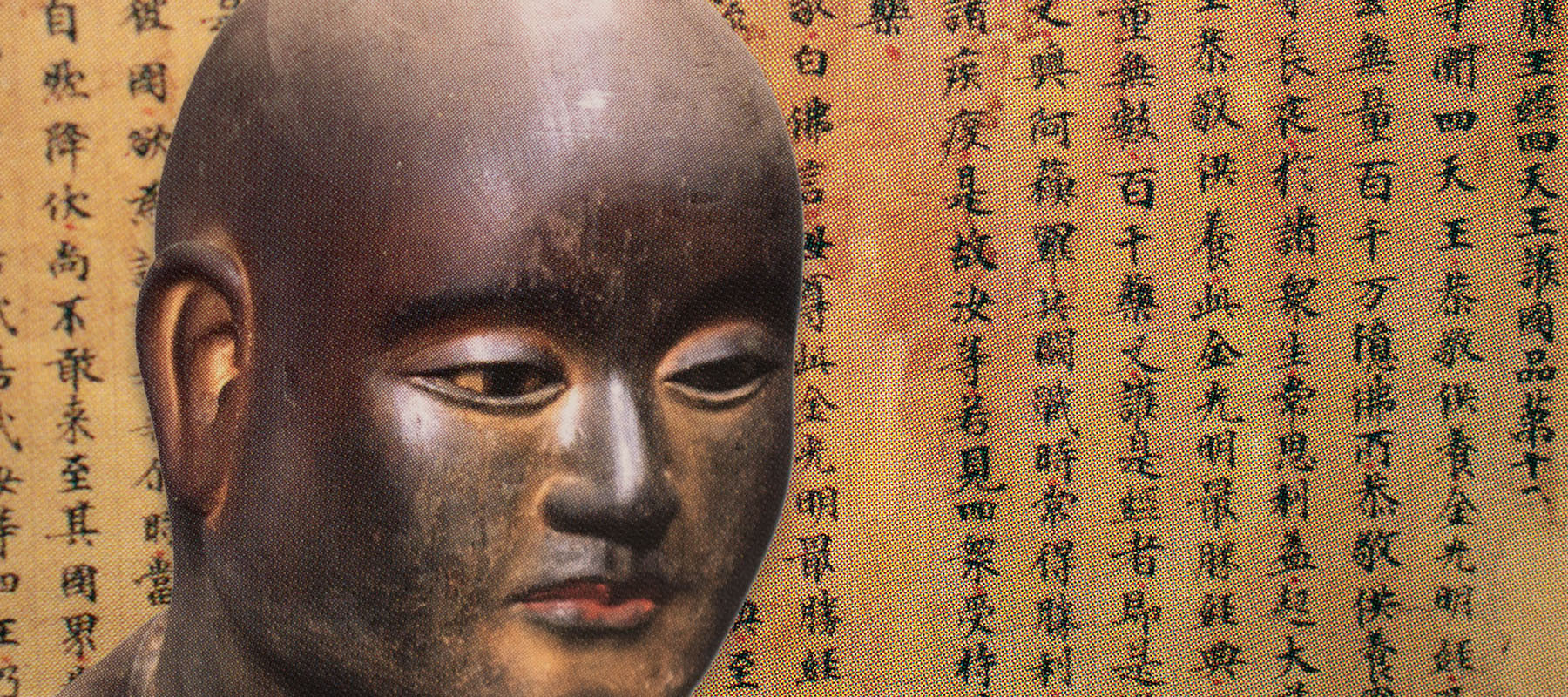

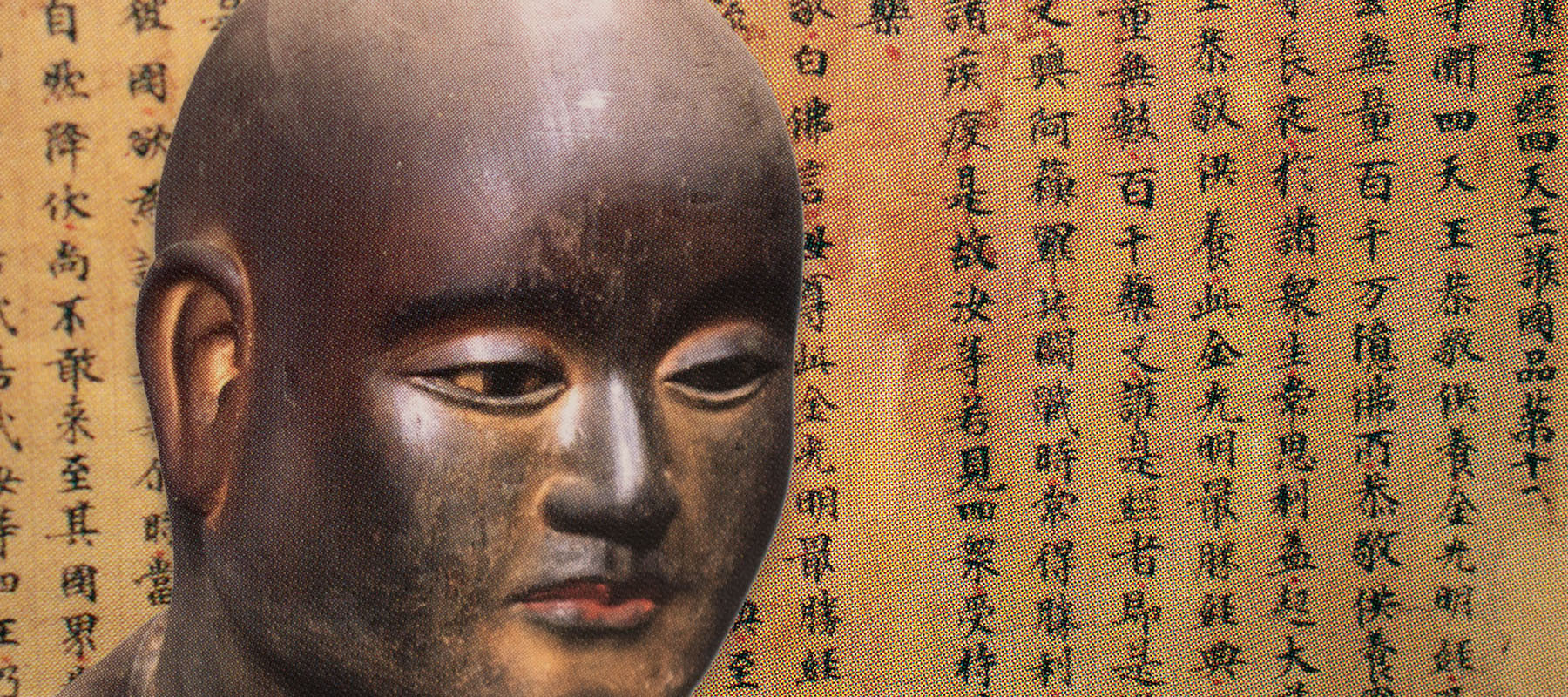

Kūkai (774-835) was one of the most brilliant and accomplished figures in Japanese history. In addition to his establishment of the monastery complex at Kōyasan and his propagation of Shingon esoteric Buddhism, he was a master calligrapher, painter, sculptor, poet, linguist, educator, and civil engineer. He wrote more than fifty works and compiled Japan’s first dictionary. He also founded Japan’s first public school and is credited by some with the creation of the Japanese kana syllabary. Often referred to by his posthumous title Kobo-daishi, he is widely considered to be the "father of Japanese culture."

Kūkai was born in the year 774 in Sanuki province (present-day Kagawa Prefecture). His parents gave him the name of Mao. The traditional date of his birth is the fifteenth day of the sixth month, but this is most likely a later attribution based on the life of an earlier patriarch of the Shingon faith.

Kūkai's father, a man named Saeki-no-Atai-Tagimi, was a member of a family of hereditary regional officials in charge of local governance and religious affairs. His mother, traditionally known as Tamayori-hime, was a member of the Ato clan of educators. Her older brother served in the capital as a personal tutor to one of the sons of Emperor Kammu (r. 781 – 806).

Kūkai's family were devout Buddhists, and their family temple was dedicated to Yakushi-nyorai, the Buddha of healing. Despite his extensive writings, Kūkai did not provide any descriptions of his own childhood, so very little is actually known about this period of his life. As is often the case for important historical figures, legends have arisen to fill in the gaps in our knowledge.

One story, for example, tells how young Mao would often fashion images of the Buddha from clay. Another describes a vision in which he sat upon a lotus and engaged in conversations with various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

When he was 15 years old, Kūkai went to the capital in order to study at the national university. After three years of preparatory lessons from his own uncle, Kūkai enrolled in the Faculty of Letters, or Myōkyōka, as it was known. For several reasons, Kūkai's admission to the university was extraordinary. For one thing, at the age of 18, he was three to five years older than most of the other students. But more significantly, even though it was one of the most powerful members of the aristocracy, Kūkai's family had been disgraced as a result of their opposition to the decision to move the capital from Nara. It is widely believed that Kūkai's uncle was instrumental in helping his nephew matriculate in this exclusive school. Of course, Kūkai's own aptitude must certainly have played a role.

The courses at the Faculty of Letters were designed for the training of high-level bureaucrats to serve the central government. They focused on the Chinese classics, as well as courses in the spoken Chinese language. Though the prospects of serving in a government post did not ultimately appeal to Kūkai, it is believed that his education at the national university helped him develop linguistic and poetic skills that he would later use to great effect.

It was during this period that Kūkai made a fateful encounter, which he later described in his work The Indications of the Three Teachings (Sangō shiki). According to his own account, Kūkai met a practitioner of Buddhist austerities who acquainted Kūkai with a secret mantra and method of meditation known as the Kokūzō-Gumonji-no-hō, which is associated with the Bodhisattva Ākāśagarbha (Kokūzō, in Japanese). The man told Kūkai that anyone who performed the Kokūzō-Gumonji-no-hō with care and perseverance would attain mastery and understanding of all sacred Buddhist texts. While reciting the Ākāśagarbha, Kūkai experienced a vision in which the Bodhisattva told Kūkai to go to China to learn the secrets of Esoteric Buddhism.

Growing disappointed with his formal education at the university, Kūkai abandoned his studies and began to devote himself to the practice of Buddhist asceticism. He shaved his head and entered the priesthood at the age of 20 (though it was not until 804 that he received official ordination at Nara's Tōdaiji Temple).

In Japan at this time, Buddhism was largely a state-sponsored religion and many of its temples were under the control of the central government. Most priests were sanctioned by and received stipends from the state. Kūkai, however, became a private priest and practiced his faith without official recognition.

Transformed by his discovery of the Kokūzō-Gumonji-no-hō, Kūkai returned to the mountains of Shikoku where he set himself to the performance of the rigorous austerities that promised to give him ultimate insight. He spent his days like a mendicant priest, subjecting himself to various forms of self-deprivation, making long forays through the mountain wilderness and engaging in extended periods of prayer and meditation.

One notable experience from this time occurred while Kūkai was reciting the Ākāśagarbha mantra. As he repeated this incantation from a cave overlooking the sea, Kūkai had a vision in which the morning star grew brighter and nearer until it finally flew into his mouth as he chanted.

The morning star, or Venus, was thought to be a manifestation of Ākāśagarbha. In other words, Kūkai had become one with this Bodhisattva. The name that Kūkai gave himself is written with the Chinese characters for sky and sea. It is thought that he may have chosen his name at this time.

In the year 797, when he was 24 years old, Kūkai wrote Indications of the Three Teachings, in which he argued for the superiority of Buddhism to both Confucianism and Taoism. Not much is known about the seven years between this work and the time Kūkai set sail for China (804).

It is believed that he spent his days studying the vast body of Buddhist scriptures. According to legend, Kūkai was not fully satisfied with the texts available in Japan at that time. He prayed fervently to have the one true teaching revealed to him.

Finally, he had a dream in which he was told about a copy of the Mahāvairocana Sutra (Dainichi-kyō, in Japanese) hidden beneath the pillars of a Kume-dera temple in Nara. Kūkai set out for this temple, and, as foretold in his dream, he found this text exactly where he was told it would be.

A pivotal chapter in the life of Kūkai began on the sixth day of the seventh month in the 23rd year of the Enryaku Era (804 AD). It was on this day that Kūkai departed for China as part of a diplomatic mission to the T'ang Dynasty.

Four ships set out from Bizen province (present-day Saga Prefecture). Kūkai, who travelled as a student monk at his own expense, was aboard the flagship, which also carried the chief envoy, Fujiwara no Kadonomaro.

Kūkai's goal in travelling to China was to learn more about the meaning of the Mahāvairocana Sutra, which he now considered to be the seminal work of Esoteric Buddhism.

He was, in short, looking for someone to teach him the meaning of this text. He appealed to Emperor Kammu and received permission to go to China with the expectation that he would remain there for 20 years.

As the Japanese ships crossed the Sea of Japan, they encountered a storm and were separated from one another. The ship carrying Kūkai and the chief envoy ended up drifting ashore at Fukien Province far to the south of their intended destination of Ningpo (formerly known as Mingzhou). Here, they encountered more trouble as the local governor was suspicious of the unexpected and uninvited foreigners. It was only after Kūkai wrote an elegant appeal in formal Chinese that the delegation was permitted to carry on.

Kūkai made his way inland to the city of Ch'ang-an, which, at the time, was the largest, most cosmopolitan city in the world.

It was also a center of Esoteric Buddhism, which had been gaining popularity in China since its introduction to the country in the eighth century.

At the time of Kūkai's arrival, the most eminent master of Esoteric Buddhism was the priest Hui-kuo (746 – 805), the abbot of Ch'ing-lung Temple.

Unfortunately, Kūkai had to wait more than five months before finally meeting Hui-kuo. And by that time, Hui-kuo was of failing health and preparing for death.

Their encounter, nonetheless, was a joyous one as Hui-kuo instantly recognized Kūkai as the person to whom he was meant to transmit the secret teachings of Esoteric Buddhism. To the surprise, no doubt, of everyone present, Hui-kuo greeted Kūkai saying, "I have been waiting for you to come...until now, there was no one to whom I could pass along the secret teachings."

Arrangements for Kūkai's formal ordination were made, and he was initiated into the secrets of the two mandala realms of Esoteric Buddhism as well as other orders. The approaching death of Hui-kuo must certainly have created an air of urgency as the master prepared his new pupil for the transmission of the precepts and teachings of Esoteric Buddhism.

Other monks worked feverishly to make copies of sacred texts and to gather together ritual implements and Buddhist images for Kūkai to take with him back to Japan. In addition to the precepts of Esoteric Buddhism, Kūkai was also instructed in the Sanskrit language of India and received training in calligraphy and poetry from the leading teachers of the day. He was a fast learner. Hui-kuo himself famously compared the way that Kūkai mastered his lessons to the process of pouring water from one vessel into another.

By the time Kūkai set sail on his return voyage in late summer of 806, he had been initiated into the most profound secrets of Esoteric Buddhism and was now the heir to the Dharma professed by the Celestial Sun Buddha, Dainichi Nyorai. He had come to China to learn about Esoteric Buddhism. He was leaving a little more than two years later as the eighth patriarch of the sect. He was only 32 years old.

To signify Kūkai's status as heir to the Esoteric lineage, Hui-kuo bestowed on him the title Henjō-kongō, which means "The Diamond that Illuminates the Four Directions."

One famous legend concerning the origins of Kōyasan says that before departing from China, Kūkai threw his ritual scepter, or "vajra," into the air toward Japan with the prayer that it would guide him to the place where he was to establish his monastery.

Kūkai traveled to China with the permission of the Japanese Emperor Kammu, and it was with the understanding that he would remain abroad for 20 years. His return in the 10th month of 806 was, therefore, a violation of imperial instructions and potentially punishable by death. To make matters more complicated, Kammu had died earlier in the year, and his son had succeeded as Emperor Heizei (r. 806 -809).

From Kyūshū, Kūkai promptly wrote to the new emperor to introduce himself and to explain the reasons for his unexpected return. In this famous letter to Heizei, Kūkai described his experiences in China and how he had become heir to the Esoteric lineage which extended back to the Bodhisattva Dainichi-nyorai. He also provided an inventory of the important Buddhist texts, images (including mandalas) and ritual implements that he had brought with him from China.

Perhaps Kūkai wrote in fear for his life, but he also had the confidence that his achievement would be recognized by the imperial court and he would be allowed to practice and propagate the teachings of which he was now the master. These teachings included the unprecedented claim that individual enlightenment and salvation could be achieved, not after countless revolutions on the cycle of death and rebirth – as most Buddhist schools maintained – but in this very existence. In addition, Kūkai sagaciously emphasized how this new religion would also offer protection to the emperor as well as peace and happiness to the state. The response that Kūkai hoped for was long in coming as he had to wait three years before finally being invited to the capital in Kyoto, where he was eventually directed to take up residence at Takaosan-ji Temple, located in the hills near the capital.

By this time, Heizei had abdicated and his younger brother now reigned as Emperor Saga (r. 809 – 823). Much to Kūkai's advantage, Saga was a great enthusiast for Chinese poetry and calligraphy, which were two things at which Kūkai excelled. Before long, the two men became close, with Saga eager to learn various calligraphic styles from Kūkai.

Kūkai's relationship with Saga helped him rise in status and estimation within the capital. Before long, he was appointed to an important post at Nara's Tōdai-ji Temple in addition to his functions at Takaosan-ji. During this time, he was also granted permission to perform rites of initiation and ordination. And soon, Kūkai's followers began to grow in numbers.

Among the many men who sought out Kūkai for his guidance was the powerful priest Saichō (767 – 822).

Saichō had traveled to China as part of the same mission as Kūkai several years earlier. In China, he became a master of Tientai (Tendai) teachings, and had established the important monastery of Enryaku-ji on Mt. Hiei. Saichō enjoyed the favor and patronage of the imperial court.

The Tendai School, led by Saichō, is ordinarily seen as a rival to the Shingon School being propagated by Kūkai. Yet, it is clear that for many years, Saichō was eager to learn from Kūkai. At one point, Saichō requested that Kūkai ordain him into the highest orders of Esoteric (Shingon) Buddhism. Kūkai, however, declined on the grounds that the Tendai Master had not undergone the necessary training. At another time, Kūkai refused to lend Saichō an important Buddhist text for fear that, without the required one-on-one instruction, Saichō would not be able to understand it properly. The friction between the two men was also aggravated by the fact that many of the followers that Saichō's sent to Kūkai for instruction ended up switching their allegiance to Kūkai and choosing to remain at Takaosan-ji.

In 816, Kūkai appealed to Emperor Saga for permission to establish a fixed home for the teaching and transmission of Esoteric Shingon Buddhism. Citing examples from India and China, he expressed his desire to build his monastery in the mountains as these provided a better environment for prayer and meditation.

Again, in his request, he emphasized the role that his sect could play in the protection and prosperity of the nation.

When Kūkai spoke of the mountains, he had one particular place in mind: "a quiet place called Kōya," surrounded by peaks a three days' journey on foot from Yoshino.

In his letter, Kūkai mentions how he had become familiar with this area during his youth when he would often wander through the region.

In less than a month after his request, Kūkai received the emperor's permission to begin his project. It is from this date that Kōyasan celebrated its 1,200 anniversary in 2017.

After first sending some of his followers to Kōyasan in the spring of 817, Kūkai himself made the journey in the eleventh month of the following year. In the spring of the next year, the 45-year-old Kūkai conducted a ceremony in which his temple was formally consecrated, but it was still a long way from completion.

While Kūkai had the government's permission, he had to go about the construction of his temple without its financial support. So Kūkai had to spend much of his time soliciting donations from local families and others. In addition to these activities, Kūkai continued his duties at Takaosan-ji. He was also occupied by Saga's request that he oversee the completion of Kyoto's Tō-ji Temple. Progress on Kōyasan was also slowed by the fact that very little work could be done during the cold, snowy winter months.

In the spring of the year 835, almost 20 years after he was granted permission to establish the temple he would call Kongō-buji, Kūkai passed away and was interred on Kōyasan to the east of the Tamagawa River at a spot he had chosen in the previous year. He was 62 years of age. He left the task of completing and managing his monastery to his nephew and follower, a man called Shinzen (804 -891).

Though we say that Kūkai passed away, faithful followers believe that he did not, in fact, die. They believe that he entered a state of perpetual meditation from which his spirit or manifestation can still arise and appear among the living to continue the work of guiding them toward salvation.

Images used here are from 弘法大師行状絵詞 ("Kōbō-daishi gyōjō ekotoba")

© 2025, k. collins